Texas Rose Festival Has History Of White Only Queens, Founded By Racist

Note: This article is part of an ongoing investigation into the racist origins of the Texas Rose Festival and its continued selection of young white women, for almost 100yrs, as their queens. Its purpose is to inspire the public to encourage the change necessary at the Texas Rose Festival Association to make possible the immediate inclusion of Black and Hispanic children and young women, regardless of class, in all varied stages, levels, in order to have a truly citywide event that celebrates all of us and our varied cultural contributions.

"I believe the separate but equal theory is sound and that it has worked out well." - Judge Ramey

What are the origins of the Texas Rose Festival? Many old Tyler families would respond with a story about Judge Thomas Boyd Ramey, Sr.[1] (aka T.B. Ramey or Judge Ramey), an attorney by trade who founded one of the best-known law firms in East Texas, Ramey & Flock, in 1922.

Press accounts and Ramey family members tell the story of T. B. becoming inspired by a personal trip to the 1933 Chicago World's Fair, whose theme was "A Century of Progress."[2] There Ramey came across an exhibit full of beautiful roses. When inquiring about the display, he learned that the flowers came from a small East Texas city, his hometown. Ramey's imagination churned with ideas to employ in Tyler.

Upon returning home, Ramey gathered interested parties within the Chamber of Commerce and began work with area garden clubs to host a Rose Festival to promote the rapidly budding local industry. Thanks to an oil boom in the area, Tyler's elite was largely unscathed by the Great Depression. But it was still essential to support local businesses. A spectacular series of events might just make all the difference.

But did the idea of what we know today as The Rose Parade originate with him?

The Rose Parade Was Not Ramey's Idea

Judge Ramey's efforts built on earlier work by the Chamber of Commerce, which staged a parade in 1909 to celebrate area growers billed as The Tyler Flower Parade. That is when the City of Tyler began its branding campaign as the "Rose Garden of America." But earlier still, in 1896, the community hosted a Battle of the Roses featuring a parade of horses and carriages all adorned beautifully with homegrown roses.

History proves the rose parade was not a unique idea for Tyler, Texas. It was an on-and-off feature dating back almost 40 years before the Texas Rose Festival, its first instance occurring when Ramey was only four years old (Ramey was born August 8, 1892, in Tyler). The entire community was familiar with the idea.

But modern history credits Ramey with the founding of the Texas Rose Festival. Tyler newspaper accounts reveal that a whole year earlier, in 1932, the Garden Clubs of Tyler and the Chamber of Commerce were both working toward the goal of a fall rose festival. The idea of what we now know as the Texas Rose Festival was probably that of Mrs. A. F. Watkins of the Tyler Garden Club. She happened to be the wife of the owner of Dixie Nursery, a prolific rose producer that also engineered and tested many new breeds and hybrids.

The Rose Festival Was Designed To Be A White Only Event

What exactly was Ramey's contribution to the local and regional culture? What was once a local event would become a nationally known affair under Ramey's direction. First, he helped organize his vision, and that of rose growers and the supportive business community, into something glorious, complete with a debutante ball, celebrated queens, and their large courts for the white elite, including rose growers.

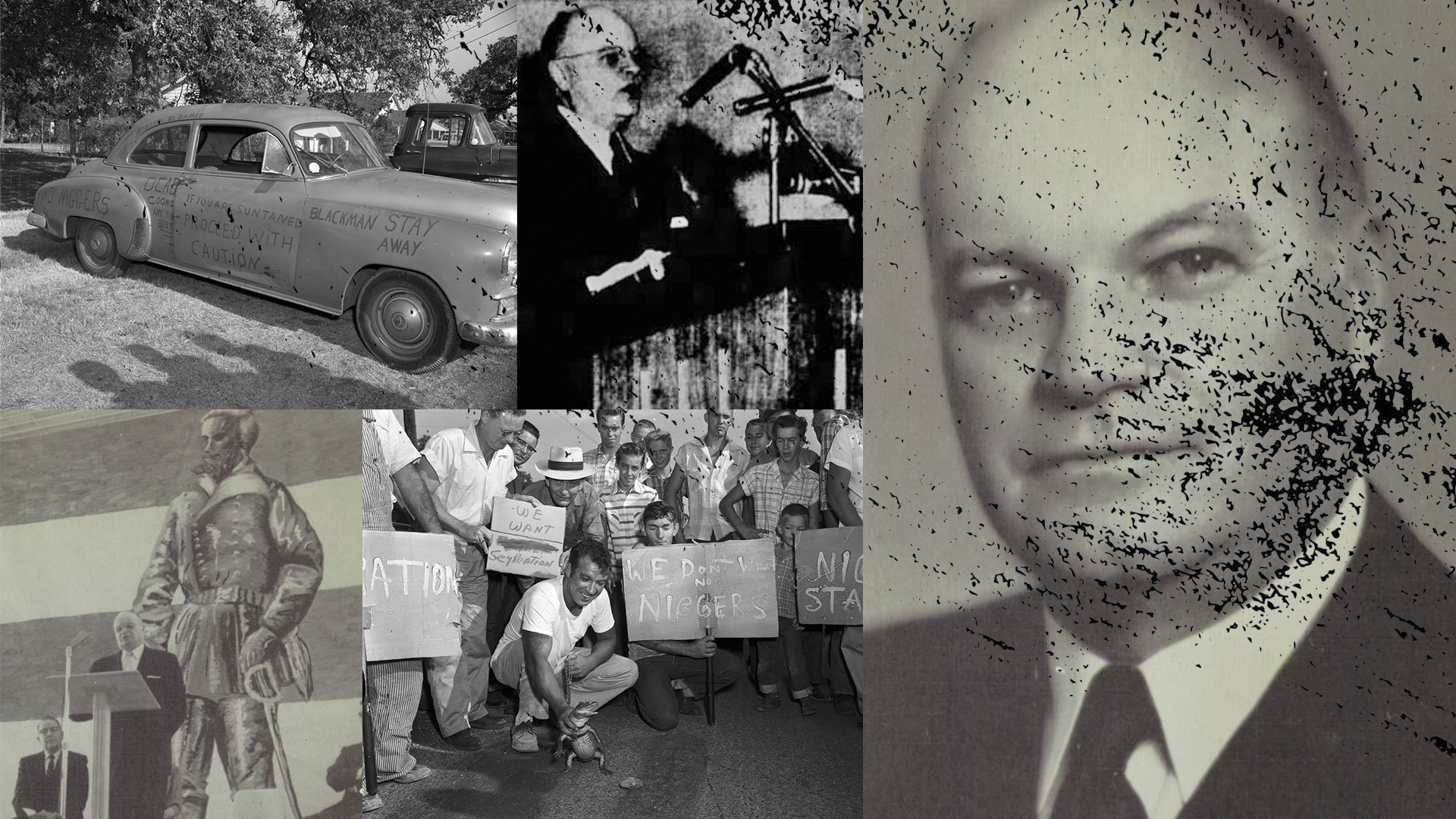

Parades and other fares would invite the rest of the town to participate, except for black people. It is important to remember that this event was born at the height of Jim Crow, America's racial caste system. Tyler was a part of that system. This legacy will haunt the festival to the present day.

Did Ramey intend to create a racist, elitist, classist event? Or better yet, what were his values? What guided his actions?

Ramey Was A Christian Segregationist

We know Ramey was a Christian. He was a member of Marvin United Methodist Church, home to many racist city leaders throughout Tyler's history. Ramey was a vital lay leader. He was also a committed segregationist, a racist, and what many would call a white supremacist. As was common in the South, Christian identity and segregation were not considered mutually exclusive. They worked hand-in-hand, especially for white supremacists in former Confederate states.

Ramey was also an incredibly devout member of several secret societies. He was a member of various lodges and temples across the state, including The Scottish Rite of Dallas, where during the 1920s, 75% of its members were Klansmen. Hiram Wesley Evans, the Imperial Wizard of America's second Klan, was also a member. The first Tyler lodge of which Ramey was a member was much the same, a known recruiting ground for the Klan.

According to Unbrotherly Brotherhood: Discrimination in Fraternal Orders by Alvin J. Schmidt and Nicholas Babchuk, these secret societies were always racist. In the 30s and throughout the Civil Rights era, these societies were ways to segregate and practice white supremacy in private.

Ramey Acted Like A Segregationist

Throughout the 30s & 40s, Ramey diligently served on the Tyler School Board,[3] where he later became its Chairman, operating for over 20yrs upholding the norms of segregated education. During this time, Ramey helped Tyler Junior College become a stand-alone entity, separate from Tyler's public school system. He became the first president of the board of trustees of Tyler Junior College, itself a segregated institution, until 1966.

But Ramey had other ambitions, namely serving at the state level. So, Judge Ramey[4] resigned from all voluntary boards in Tyler to dedicate time and attention to his campaign for the State Board of Education. Then, finally, he won and began his almost decade-long service to Texas-wide education during desegregation[5]. In 1954, after the Brown v Board of Education decision reversed the legalized segregation of Plessy v Ferguson, Ramey advised the segregated school districts on what actions to take.

How did Ramey feel about the Supreme Court decision? While serving as the Chairman of the State Board of Education, he said he was "disappointed." But, Ramey said, "I believe the separate but equal theory is sound and that it has worked out well, to the advantage of all the people - both white and colored."

But if you examine the record, specifically that of Tyler's schools under Ramey's tenure, the court was right, "separate education facilities are inherently unequal."

Examples include the 1939 school board denial of funds to build a shed-like structure with hot and cold running water at Tyler's all-Black Emmett Scott High School. The school's P.T.A. wanted to provide hot lunches to its students, which white schools made possible for white students. But the board denied the request. Why? A white school needed an auditorium. Another example dates to 1945 when the school board displaced the black high school students to preserve the "dividing line between whites and negroes" formally instituted by Tyler's apartheid-esque city plan in 1931. The black high school was in white territory.

What kind of man would be disappointed in desegregation, making society fair, just, and charitable to and for all? History teaches many Southern men born in the tail-end of the Victorian era held on tightly to white supremacy; it was one of its most closely held values. But, of course, Ramey wasn't alone. He was a man of the people. Much of Tyler believed the same. Ramey, a son of Tyler, was indeed the favorite son, maybe the perfect son, for defending the white supremacist values of its community.

Ramey's Support Of Segregationist Otis T. Dunagan

Ramey wasn't alone in his defense of white supremacy. His friend (and fellow volunteer of a Rose Festival committee), Otis T. Dunagan[6], also a judge in the model of other Southern Christian racist jurists, upheld the bigoted status quo. Dunagan is known best for his decision which rendered the N.A.A.C.P. of Texas ineffectual.

As N.A.A.C.P. lawsuits made strides toward desegregating Texas, enraged white Texans claimed the organization was using subversive tactics and operating illegally in the state. The Texas Attorney General filed a lawsuit against the civil rights group in Tyler, Texas.

Why file in Tyler? Was it because the community was known for its unwavering commitment to white supremacy? Was it because of Judge Dunagan's Jim Crow-friendly convictions which would have become well-known across the state during his tenure as a legislator?

Incapacitating The N.A.A.C.P.

Thurgood Marshall, the N.A.A.C.P.'s best and brightest attorney, came to town to defend the nonprofit. According to accounts, Marshall witnessed a courthouse surrounded by members of White Citizens Councils[7] and other racist groups from across the state all waving Confederate flags. Their support for segregation was clear. Inside the courtroom, representatives from the Alabama A.G.'s office (Louisiana and Georgia were also keeping up with the case) observed, hoping to learn how to prosecute a similar lawsuit against the N.A.A.C.P.

The legacy of the South was alive and well in Tyler and throughout the state. Segregation continued unabated with the assistance of Judge Dunagan[8], Ramey's racist friend. The judge ruled in favor of the State leading to the closure of 113 NAACP chapters in Texas and threatening their existence nationwide. Now, the N.A.A.C.P. could not involve itself in significant political and legal matters affecting African Americans throughout the state. Because Dunagan's decision was unconstitutional, the Supreme Court eventually ruled that Texas and other states could not limit or impede the N.A.A.C.P.

Marshall had the last laugh. He was appointed to the United States Supreme Court more than a decade later. In 1977, Jim Plyler, Tyler I.S.D.'s superintendent, moved to expel children of impoverished migrant families in the district unless they first paid tuition. Migrant families sued. Marshall joined Justice Brennan's majority opinion ruling that the 1977 Plyler v Doe suit, another racist Tyler-based case, disadvantaged migrant children. Today, Tyler I.S.D. is majority Hispanic.

A few years after this case, an opportunity opened a seat on the State Court of Criminal Appeals. His friend and fellow Tylerite, Judge Ramey, stepped forward to help run the winning campaign. Toeing the line was rewarding.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Educated During Jim Crow - He graduated Valedictorian from Tyler High School in 1909, received a B.A. degree from the University of Texas in 1913, and attended law school at Columbia University for a year before he received a law degree from the University of Texas in 1915.

[2] As a sign of the times, the Smithsonian magazine contributor Jesse Rhodes noted that "Exhibits at the fair were rife with the regrettable iconography of mammies, happy slaves and extreme Western visions of tribal culture. Even worse were the discriminatory business practices against black attendees."

[3] Ramey served on the school board from 1928 to 1949.

[4] A year after Ramey resigned from the Tyler school board, an elementary school for only white children was built and named in his honor. Ramey Elementary School is now a minority-majority school.

[5] Ramey served on the SBOE from 1949 to 1958.

[6] Dunagan served as chairman of deacons at Tyler's First Baptist Church, overseeing 100+ deacons at the megachurch.

[7] White Citizens Councils in Texas were motivated by protecting segregation and served as a more palatable modern Ku Klux Klan-type white supremacist organization.

[8] In 1933, Otis T. Dunagan was elected to the state legislature for Upshur County (Gilmer). Committees on which he served were responsible for Jim Crow laws that created separate sanitariums for Black healthcare and railcar segregation by race.